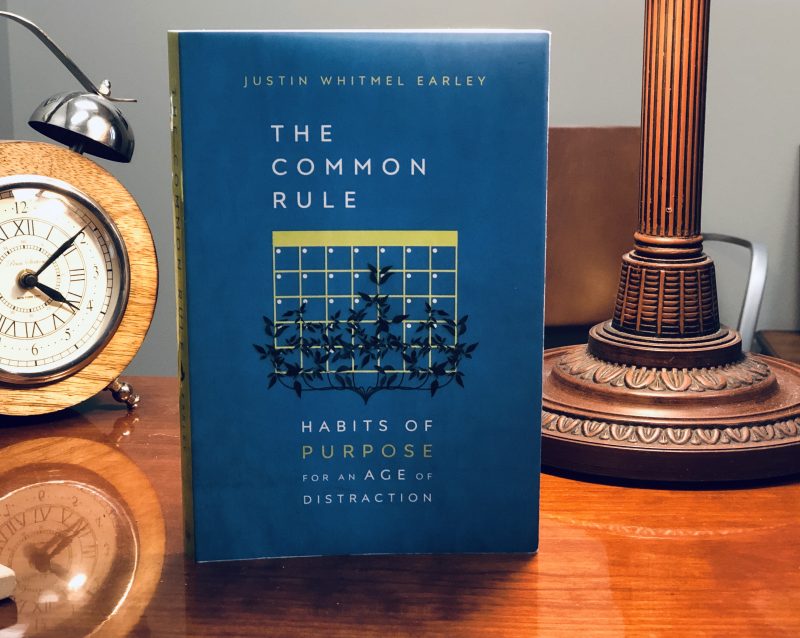

Justin Whitmel Earley. The Common Rule: Habits of a Purpose for an Age of Distraction. IVP Books, 199 pages, $18.00.

The Common Rule is the kind of book that, if its prescription is taken seriously, can probably save lives. I mean that literally. A passing awareness of the news is enough to know about the surge in depression, anxiety, and suicide among millennials, particularly professional, college-educated ones. Without any sweeping claims or controversial analysis, The Common Rule meekly presents a powerful, life-saving antidote to a restless culture that’s choking on minutia and starving for meaning. One’s only quibble would be that this is more a potent dose than a full supply.

Near the beginning of his book, Justin Earley recounts the story of a severe nervous breakdown. While an ambitious career was beginning in law school, Earley intentionally structured his life around being as available, as “connected,” and as active as possible. Convictionally, he was a Christian who believed in the worship of Jesus, but habitually, he became a worshiper of doing. “I now see that my body had finally become converted to the anxiety and busyness I’d worshiped through my habits and routine. All the years of a schedule built on going nonstop to try to earn my place in the world had finally rubbed off on my heart.” This insight is crucial to the logic of The Common Rule: We are being formed not only in the image of what we believe but what we practice. Our habits don’t just reveal our beliefs, they shape them. A more theologically profound book on this topic is James K.A. Smith’s You Are What You Love, but where Smith is most concerned about changing our understanding of and attitude toward habit, Earley offers an impressively thorough, and helpfully actionable, set of practices.

The “common rule” that the title refers to is a set of four daily habits and four weekly habits. Together, the eight habits form a concise, systematic rule of life for maintaining spiritual, relational, moral, and physical health. The greatest strength of the Common Rule, its specificity, is also its greatest weakness. Many of the practices of the Common Rule depend on a certain middle-class, information-economy lifestyle that many but not all Christians share. For example, the weekly rule “Curate media to four hours” is perhaps too rife with an American, upwardly mobile subtext to really mean something to especially poor or especially non-Western believers. Similarly, much of the book’s effectiveness will depend on how much readers feel distracted by digital devices or burnt out by an oppressive daily rhythm.

But of course, many American Christians do feel that way, and for them too many books about intellectual health in an omni-connected era are little more than data points mixed with self-evident truisms. Even the good books tend to try too hard to be “revolutionary” and end up offering a binary choice between technology and flourishing. A helpful, recently released general market book on this topic, Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism, is persuasive and insightful, but several of Newport’s recommended practices are extreme and likely unfeasible for the very readers who most need their benefits.

Earley’s approach is far more about creating habits than erasing them. For example, Earley rightly extols interpersonal relationship in pushing back against the disembodied communication of the internet. The Common Rule thus commends one daily meal with others and one weekly, hour-long conversation with a friend. These may sound like minor, even trivial, guidelines. But that’s exactly the point. Ours is a technological time in which even the most trivial human interactions are being annihilated. Just as how we never stop needing basic theology and spiritual disciplines, we never stop needing just an hour’s worth of conversation with a being who can look us in the eye, not in the avatar. In refusing to make The Common Rule a revolutionary manifesto, Earley has made it into something more personal, more practical, and more helpful.

Earley understands that the “distraction” at the heart of 21st century life is actually a deep confusion about what a person is. An exclusive diet of digital relationships and trivial mass media frustrates and grieves us because human beings are image-bearers created for glory, not efficiency machines. The first practice of The Common Rule is a kneeling prayer three times per day, a habit that physically reminds us of the dust from where we come and of the Creator to whom we must speak and from whom we must hear. Earley’s chapter on prayer convicted me deeply of my own indifference toward the presence and word of God throughout my day. Something is going to frame my morning, afternoon, and evening. If that is not time with the Lord, what will it be?

My only critique is the somewhat low-shelf theological reflection. There are some really good sections about identity formation and beholding the world (“We become what or who we reflect…We can’t become ourselves by ourselves. The way we discover ourselves is by staring at someone else.”), but the book’s heavily practical focus leaves some important issues unsolved. I would have loved to see a chapter that weaved the 8 Common Rule practices into a thread of worship. Habits always coexist beside loves, and the Christian life defines flourishing in terms of worshiping the One who is worthy of worship, and patterning our lives worshipfully. One hopes for a future expansion of The Common Rule along these lines.

For a long time I believed that spontaneity was a synonym for happiness. As I’ve gotten a little bit older, I’m come to realize the truth at the heart of The Common Rule: My heart needs people, places, and practices that sink deeply into the ground of my life and stay there. For desperate believers who are tired of spiritual lingo peppering life that’s really devoted to becoming more like a machine, The Common Rule offers a badly needed alternative. Here’s hoping this conversation continues and does not stop anytime soon.